The Bucket Stops Here

UKRI’s new funding framework takes a stab at classifying budgets – but doesn’t yet govern research

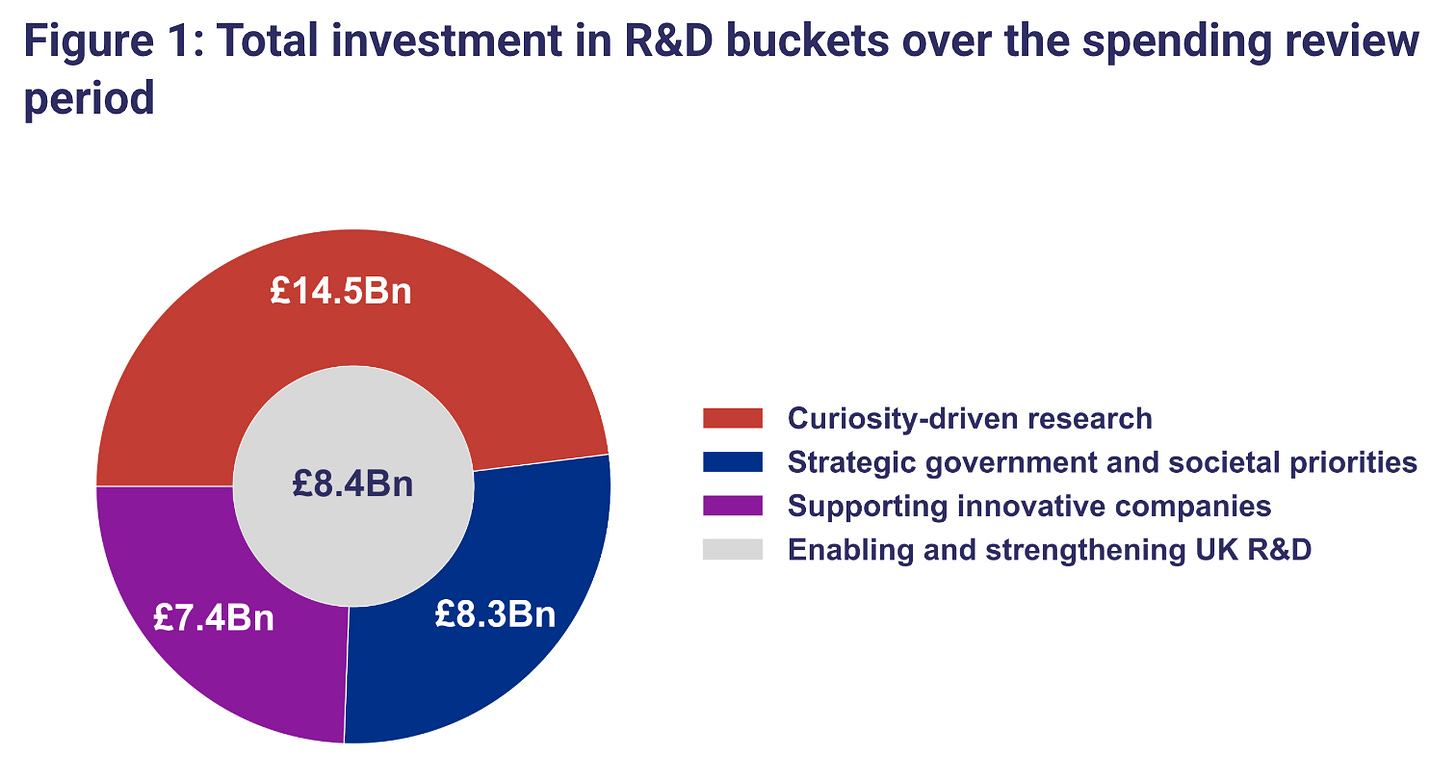

On 17 December, UK Research & Innovation published its Budget Allocation Explainer – the first detailed implementation of the three-bucket framework that Science Minister Lord Vallance has been developing since taking office. The document was presented as “the most significant change in how UKRI allocates funding and manages its budgets since the organisation was established.” It assigns £38.6 billion across four categories over the Spending Review period, creates cross-UKRI programmes for the Industrial Strategy sectors, and promises further strategic documents in spring 2026.

(Reminder: the framework splits the R&D budget into funding for three distinct types of activity: (i) curiosity-driven, fundamental research; (ii) research that’s aligned to government or societal priorities; (ii) business-led innovation.)

In early February, UKRI CEO Professor Sir Ian Chapman appeared before the Science, Innovation and Technology Select Committee to explain the new framework and to address concerns about funding pressures at the Science & Technology Facilities Council. The session offered the first opportunity to see how the bucket framework holds up under scrutiny – not just as a set of budget tables, but as a governance settlement that the sector can understand, that parliament can hold to account, and that connects public investment to research outcomes.

This piece argues that the Explainer and the subsequent exchanges reveal a gap between what the bucket framework claims to be and what it currently does. The framework classifies budgets, but it does not yet govern research. And the consequences of that gap are already becoming visible in the research base.

In November, before the Spending Review and Explainer were published, I proposed ten tests that the bucket framework would need to pass to be meaningful. These tests weren’t meant to be gotchas; I was clear in the piece that the bucket framework has real potential to help with coherence and prioritisation in the science budget. Rather, my tests were presented as the minimum conditions for the framework to function as a governance settlement rather than just a taxonomy. In sum: does it state what problem it solves? Does it specify distinct governance modes for each bucket? Does it provide a doctrine for research transitioning between buckets? Does it create a credible mechanism for protecting discovery?

The Explainer is the first opportunity to assess how the framework has been operationalised. It engages seriously with almost none of these questions.

What the Explainer says

A fair summary first. The Explainer allocates UKRI’s £38.6 billion across four categories. Bucket 1, curiosity-driven research, receives £14.5 billion. Bucket 2, strategic government and societal priorities, receives £8.3 billion. Bucket 3, supporting innovative companies, receives £7.4 billion. A fourth category, “enabling and strengthening UK R&D,” receives £8.4 billion for infrastructure, talent, institutes and facilities.

Each Industrial Strategy sector gets a Senior Responsible Owner (SRO), drawn from the executive chairs of UKRI’s councils, who leads a cross-UKRI programme board. In addition, we get an extremely high-level breakdown of what’s going into each bucket (how much per sector, how much for QR, how much for compute, and so on.)

Should we wish to compare these numbers with what was being spent before, the Explainer is explicit: “it is not possible to directly compare these allocations to previous budgets” (and we will return to this).

What the Explainer does not contain is any governance architecture. There is no description of how the buckets operate differently from one another, nor is there any account of how boundaries between them are managed. There is no discussion of how risk appetite or accountability varies across modes, nor are we provided with a doctrine for what happens when research transitions from one bucket to another.

It is, essentially, a set of budget tables with brief contextual framing. Further strategic documents are promised for spring 2026 – for now we have the high-level numbers and that’s about it.

What the select committee revealed

Chapman’s appearance before the committee is worth examining because it illuminates problems that the Explainer’s careful prose obscures.

The most important is comparability of budgets over time. The Explainer says it’s impossible – but if a framework cannot be measured against its starting point, then it cannot be held accountable for its results. Under questioning from the committee chair, Chi Onwurah MP, Chapman’s position shifted: comparison was “not possible,” then “possible, of course, but it would take a lot of effort and backwards bookkeeping,” then he offered a high-level estimate anyway – roughly 50/25/25 between curiosity, applied research, and company support (setting aside the enabling layer) – and conceded that grant-level data exists and could in principle be attributed to the new buckets. The committee asked him to return with both the high-level estimates and a fuller explanation of why more detailed comparison is difficult. He should.

The 50/25/25 estimate is itself revealing. If the historical split is “basically the same” as the new allocation, what has the reform actually changed? Chapman’s answer was indeed all about governance: coherence, accountability, and single programme owners who can be held responsible. That is a reasonable ambition that we should support. But the Explainer’s money tables don’t measure up. We may get more detail in spring 2026. Until then, we have a reform that, by the CEO’s own account, hasn’t changed allocations, and hasn’t yet specified the governance it promises. As Onwurah put it: “We are giving you a pass for where you are now.”

There was also a brief exchange about the fourth bucket – the £8.4 billion enabling layer covering infrastructure, talent, and international subscriptions. Chapman described it as something that “just pro-ratas to the other three.” But we should push back on this – a quarter of UKRI’s total allocation cannot be dismissed as a proportional residual. Infrastructure investment, doctoral training, and international facility subscriptions each have their own particular justifications and approaches, which do not distribute evenly across curiosity, strategy, and business support. As I argued in November, cross-cutting enablers need their own governance layer, not an accounting afterthought.

QR: the central exhibit

The single most consequential decision in the Explainer is the classification of quality-related research (QR) funding. All £8.9 billion of it, over the SR period, is placed in Bucket 1: curiosity-driven research.

This decision shapes everything else. With QR included, Bucket 1 is the largest category by a wide margin – £14.5 billion, nearly double Bucket 2’s £8.3 billion. Without QR, Bucket 1 would be approximately £5.6 billion: still substantial, but no longer dominant, and uncomfortably subscale relative to the other buckets.

The political utility of this classification appears straightforward. A £14.5 billion curiosity-driven budget allows the government to say it is investing generously in blue-skies research. Without tucking in QR, it’s much harder to sustain that narrative – particularly when the fastest-growing budget lines are all in Buckets 2 and 3.

But there’s a problem with this. Under questioning at the select committee, Chapman used QR as his primary example of why backward comparison is difficult. “If I said, all of the money that we spend on quality-related research,” he told the committee, “that is for sure contributing to all three buckets.” He continued: “It represents £10 billion or £11 billion of our spend. It goes in multiple different directions.”

So parliament is now told that QR contributes to all three buckets – just weeks after UKRI published a document placing all QR in Bucket 1. The UKRI CEO was simultaneously defending the classification and undermining it. The committee did not quite catch the significance of the admission. Readers of this piece should.

QR is allocated through the Research Excellence Framework. REF assesses research of all types – not just curiosity-driven research – and spends enormous effort measuring the impact of that research: its real-world effects on policy, industry, health, and culture. Impact case studies, which account for a quarter of the REF assessment, reward exactly the kind of strategic, applied, partner-engaged work that DSIT says it wants more of in Buckets 2 and 3. Universities use their QR funding to sustain research groups working on everything from clinical trials to industrial partnerships to policy analysis. Classifying all of this as “curiosity-driven” is a massive fudge.

The Explainer gets around this by never defining “curiosity-driven.” But the term is not ambiguous. Curiosity-driven research is research motivated by the intrinsic desire to understand something. The government chose that label, not “investigator-led” or “non-commissioned” or “responsive mode,” presumably because it carries a particular weight: the image of foundational inquiry, of researchers following questions wherever they lead. Having chosen the label, the Explainer then uses it to mean something quite different: research that doesn’t fall within a government-identified priority area. That is a description of where the funding sits in UKRI’s portfolio, not of the research it supports.

This might seem like I’m arguing the semantics of government comms. But if the buckets are meant to be about improving the way we actually do research in the UK, then the labels need to describe the research accurately. A framework that cannot tell the difference between “the government hasn’t prioritised this” and “this was motivated by curiosity” does not understand what it is governing.

QR is a funding stream that supports the capacity of universities to self-organise around government priorities without being centrally directed. The civic university agenda, industrial partnerships, place-based innovation strategies, and addressing societal challenges – all of this happens through institutional initiative, funded significantly by QR. If all of this sits comfortably under “curiosity-driven,” then we have hollowed out a word that means something real – about motivation, about inquiry, and about what it feels like to follow a question into the unknown – and replaced it with an administrative residual category. This is ugly. And the flip side is that the system gets no credit for strategic delivery that isn’t centrally directed, which in turn makes the case for ever more central direction look stronger than it should. This is dangerous.

How did we end up here? Through a convergence of institutional convenience that nobody has an incentive to disturb. The sector, led by the Russell Group and others, has advocated for QR as discovery funding for years, presumably because framing it as foundational research is seen as the safest political argument for protecting it from cuts. The Russell Group’s advocacy materials lead with graphene, genomics, and cosmology – science as pure as the driven snow. Additionally, HM Treasury’s internal spreadsheets classify QR as “core research”, presumably because it fits nicely into the 1980s basic research market-failure-response mindset that permeates Whitehall, but also because it’s formula-based and not centrally directed. So DSIT naturally follows suit, slotting QR into Bucket 1 because both the sector and the Treasury have already told them that’s what it should sit – no harm, no foul.

Nobody in this chain has an incentive to say: “QR funds a huge amount of strategic, applied, and commercially oriented activity – and that’s a feature, not a bug.” But the Russell Group’s own position gives the game away. Their December 2024 briefing recommends that “when new R&D commitments are introduced, QR funding should be uplifted to ensure the research base is supported to deliver on new priorities.” Wait a minute – if QR were purely about curiosity, why would it need uplifting for strategic priorities? The recommendation implicitly concedes that QR is delivery capacity for government objectives – which of course it is, but this is precisely the reason it shouldn’t be classified as though it were all blue skies.

The governance consequence of this misclassification is significant. If QR is treated as undifferentiated curiosity, there is no mechanism within the bucket framework for connecting problems in the research base – declining momentum in strategically important fields, for instance – to the funding instrument that actually sustains university capacity in those fields. The framework creates a structural disconnect between the diagnostic and the instrument that could respond to it.

Quantum: the mirror image

If QR illustrates the problem of strategic research being classified as curiosity, quantum technologies illustrate the reverse. Quantum receives over £1 billion across Buckets 2 and 3 in the Explainer. There is a National Quantum Strategy, a ten-year programme track record, and an SRO in the form of Charlotte Deane, EPSRC’s executive chair. By the framework’s logic, quantum is strategic.

But much of the underlying physics – error correction, topological quantum states, fundamental materials science – is as curiosity-driven as anything EPSRC funds through responsive-mode grants. And if the National Quantum Strategy didn’t exist, I’d bet that much of this work would be happening anyway, funded through standard EPSRC grants, and classified as Bucket 1. So the bucket follows the administrative wrapper, not the character of the inquiry.

Chapman told the select committee that quantum is his “poster child.” He described it as having “a really clear strategy,” internationally differentiated companies, and a ten-year track record of STFC, EPSRC and Innovate UK working together coherently. For what it’s worth, I strongly agree with Ian on this – if Bucket 2 is to make any sense at all, then UKRI could do much worse than looking at the National Quantum Technologies Programme as a benchmark for how to invest strategically in a field.

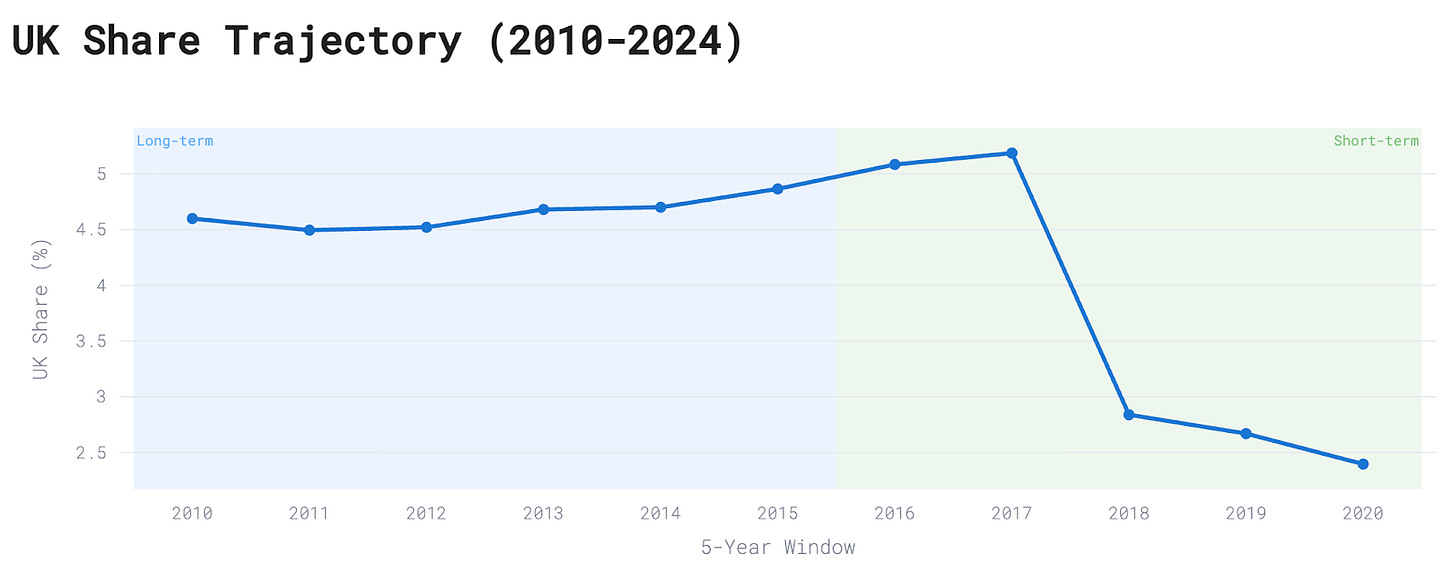

But analysis of UK research share across 4,516 topics using OpenAlex publication data tells a more complicated story. Quantum information and cryptography shows the UK losing significant ground to our global competitors: the UK’s share of publications in this field has roughly halved from approximately 5% in the period 2017-2021 to 2.3% today.1 Publication share is not the only measure of research health, of course, but it is a signal that warrants explanation, and the bucket framework currently has no mechanism for providing one.

The obvious pushback is: quantum has a multi-billion pound programme across Buckets 2 and 3, with an SRO, a ten-year track record, and investable companies to show for it – so what exactly is the problem? The problem is that both things appear to be true simultaneously. The programme is delivering on its own terms, while the UK’s position in the global quantum research landscape appears to be deteriorating.

There are several possible explanations. The programme may have deliberately shifted effort from publications toward commercialisation, in which case declining research share is an acceptable trade-off – and someone should say so explicitly. Or the programme may be successfully translating existing research while the pipeline of new foundational work thins underneath it, in which case there is a problem that will not be visible until the pipeline runs dry. Or there could be some other explanation – I suspect we don’t know.

Whatever the reason, the buckets framework provides no way of asking the question. All we know is that the SRO owns the programme and is accountable for programme outcomes. For quantum, the SRO just so happens to be the executive chair of EPSRC, the council which funds the bulk of upstream and downstream quantum research. But even if this led to all kinds of accidental synergies, Charlotte Deane isn’t structurally accountable for the relationship between the directed programme and the broader health of the research field that feeds it – a relationship that spans the boundary between Buckets 1 and 2. As we have seen, the bucket framework has no mechanism for managing that boundary.

This matters because Chapman is presenting the quantum SRO model as the template for all Industrial Strategy sectors. If the model works by delivering coherent programmes while remaining blind to what is happening to the foundational research underneath, then generalising it across the system embeds that blindness everywhere. Because Charlotte Deane is managing quantum in both bucket 1 and bucket 2, this may end up sorting itself out in practice; but in other areas (such as advanced manufacturing or clean energy) this won’t necessarily apply.

STFC: what happens when the framework meets reality

On 28 January, Michele Dougherty wrote to the particle physics, astronomy and nuclear physics (PPAN) community with difficult news. STFC’s PPAN budget would need to fall to around 70% of its 2024-25 level. Individual projects were being asked to model flat cash and reductions of 20%, 40% and 60%, and to identify the funding point at which they become non-viable.

Four days later, Chapman published an open letter to the wider research community. It was admirably direct. STFC’s core budget is holding roughly flat – £835 million to £842 million over the SR period – but costs have risen beyond what the settlement can sustain. Energy prices and exchange-rate movements alone added over £50 million a year, and an ambitious programme from the previous Spending Review had accumulated commitments that the current budget cannot cover. £162 million in cumulative savings must be found by 2029-30.

Credit where it is due. Both letters represent a quality of directness and personal ownership that is rarer in UKRI communications than it should be. Chapman signs his letter “Ian.” Dougherty asks the community to “work with us” while being clear about the severity of what is coming. These are leaders grasping the nettle of a problem that’s accumulated over years. Chapman is explicit that “the situation at STFC is unique among the UKRI councils” and should not be confused with the broader bucket reforms.

But we should notice what the bucket framework contributes to understanding this situation: absolutely nothing.

STFC’s activities span multiple buckets. Its applicant-led PPAN grants sit in Bucket 1. Its international subscriptions – CERN, the European Southern Observatory – sit partly in Bucket 4. Its facilities and national labs seem to straddle Buckets 1, 2 and 4. Its applied and innovation work feeds Buckets 2 and 3. When STFC faces a £162 million cost pressure and must cut PPAN grants to around 70% of their recent level, which bucket is actually absorbing the pain? The honest answer is that the buckets are invisible at the point where the trade-off is actually made. The prioritisation happens within STFC, impacting activities that span across the entire framework, and mediated by the executive chair’s judgement and the Science Board’s advice.

Dougherty’s letter even acknowledges this implicitly. “These difficult funding decisions should be viewed alongside emerging opportunities including new investments in digital infrastructure and compute, and future funding through other UKRI buckets, which could benefit the PPAN community.” The buckets are being invoked as a consolation – perhaps the community can win money back through Bucket 2 or 3 – rather than as a framework that governs the decision itself.

This is the comparability problem in live action. The committee chair asked how parliament can scrutinise changes in spending if backward comparison is impossible. The STFC situation shows that even forward transparency is compromised. The actual decisions happen below the bucket level, inside councils, where the old system of disciplinary portfolio management still operates. The buckets are a reporting layer only.

And then there is the “protected” claim. Chapman’s open letter repeats the central assurance: “support for curiosity driven research is protected across the SR period, comprising around 50% of our investment.” Dougherty’s letter frames PPAN as “now operating fully within STFC’s curiosity-driven research portfolio.” So: curiosity is protected. PPAN is curiosity. And PPAN is facing being cut to 70%. All three statements are held to be true simultaneously.

The resolution is that “protected” means the aggregate Bucket 1 number holds. Within that aggregate, individual disciplines can be cut dramatically – particle physics, astronomy, nuclear physics – as long as the total stays roughly constant. The bucket protects a budget line, not the research it contains.

To be clear: this is not a criticism of the specific decision to reduce PPAN funding. That may well be the right call given STFC’s cost pressures, and Chapman is absolutely right that hard choices are unavoidable within a constrained envelope. My criticism is that the framework’s definition of “protected” is so coarse-grained that it is compatible with 30% reductions in specific disciplines while maintaining the headline assurance that curiosity-driven research is safe. Speaking at a Campaign for Science and Engineering event earlier this week, Chapman stressed that UKRI is still in a solicitation phase, gathering impact information and priorities before final decisions are taken through council and advisory routes. But given the scale of cuts under consideration, “curiosity-driven research is protected” may turn out to mean something much less reassuring than it sounds.

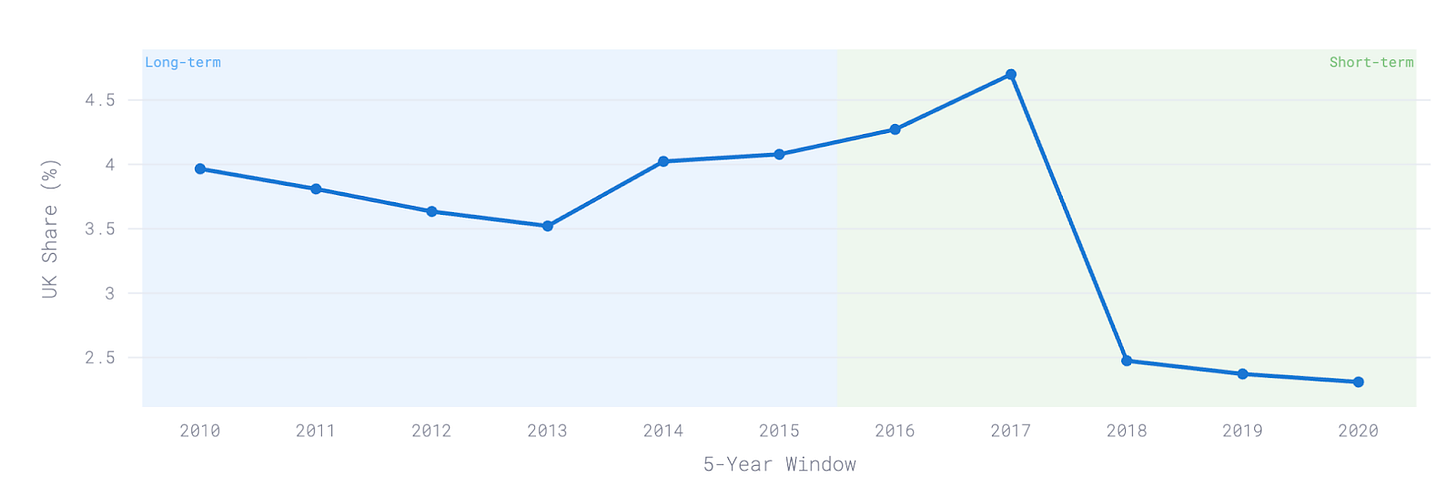

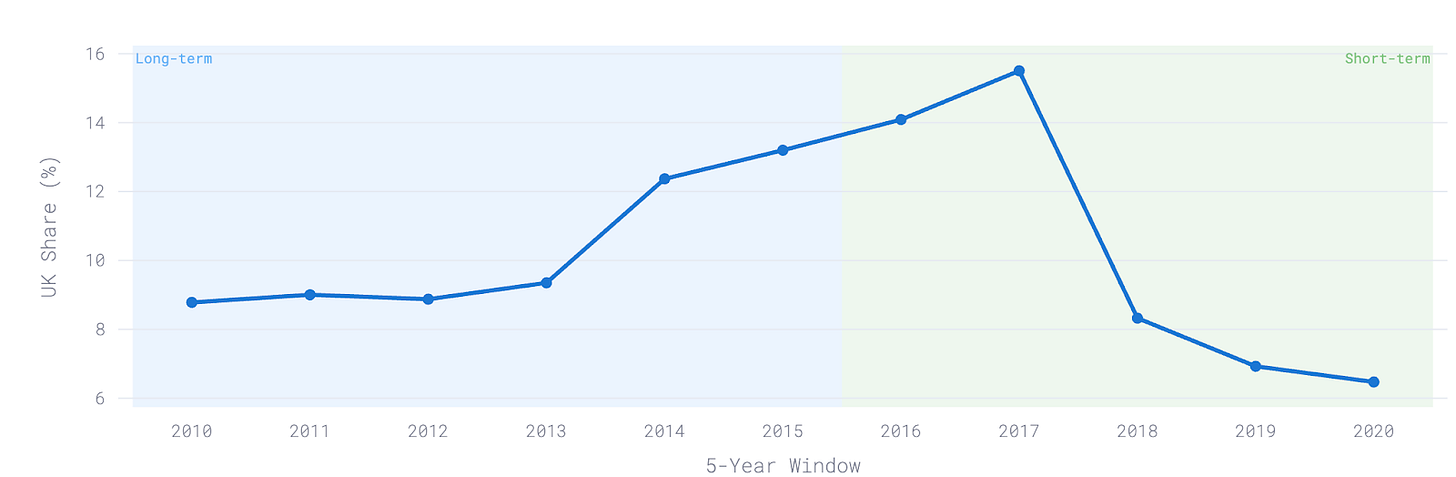

The bibliometric data adds an uncomfortable dimension. The STFC disciplines are precisely the areas where UK research share is already in rapid retreat. Particle physics saw its UK share fall from approximately 4.7% in the 5-year period before 2021 to 2.3% the period to 2024, with momentum reversing from slightly positive historically to clearly negative in recent years. In the ‘galaxy formation and evolution’ research topic, UK share fell from around 15.5% to 6.5%. These trends predate the current cuts. The PPAN reductions will likely accelerate declines that were already under way.

Perhaps that’s OK. Perhaps the UK doesn’t need to participate as much in big physics as we once did, and the STFC cuts simply come in the wake of that hard fact. But the bucket framework has no mechanism for flagging this interaction. There is no system-level process that says: particle physics is in rapid retreat, and now we are proposing a 30% budget reduction on top – is this a deliberate strategic choice, or an unintended consequence of cost pressures elsewhere in STFC? The decision is being made inside STFC’s portfolio, not at the system level where the interaction between strategic intent and research trajectory could be examined.

Dougherty’s letter does promise that “UKRI and STFC will continue to monitor the health of disciplines and maintain flexibility to adapt investment plans.” This is welcome language. But there is no published framework for what monitoring the health of disciplines means in practice, what metrics are used, what triggers escalation, or who is accountable if a strategically important field enters terminal decline while remaining nominally “protected” inside Bucket 1.

The STFC situation illustrates a general point. The bucket framework operates at a level of abstraction that is disconnected from where prioritisation actually happens. Real trade-offs are made within councils, between disciplines, between facilities and grants, between inherited commitments and new opportunities. The buckets classify the results of those trade-offs after the fact. They do not govern them.

So what are the buckets actually doing?

At the CaSE event this week, Chapman offered the clearest rationale I have yet heard for why three buckets might matter: if UKRI stops forcing every proposal through multiple lenses at once, then curiosity-driven funding can take more genuine risk, rather than converging on a “grey middle” of projects that are simultaneously publishable, impactful, and plausibly growth-adjacent. That is a serious ambition.

And in fairness, if the buckets function simply as a way for UKRI to organise its internal budget management – knowing when to be more or less hands-on – they may still prove useful. The government never explicitly promised distinct governance modes with different logics for agenda-setting, accountability, and risk tolerance: that was the standard I argued for in November, not one that DSIT set for itself.

But the bucket framework did not arrive as a modest internal management tool. It was presented as the most significant change since UKRI’s establishment, restructuring the entire budget as the operational expression of the Industrial Strategy, with explicit demarcation and protection for curiosity-driven research. When tested against the weight of this, what we find is a series of fudges: the strategic work that QR supports gets classified as curiosity-driven, quantum is curiosity-driven research classified as strategic, and STFC disciplines are “protected” research facing a cut of 30%.

As things stand, the buckets are not really about research at all – they are about administrative control. “Curiosity-driven” means money that the state doesn’t direct. “Strategic” means money wrapped in a programme with an SRO. These are descriptions of the funding approach only, not of the research it supports. A quantum physicist working on error correction is very likely doing curiosity-driven research by any reasonable definition, but it sits in Bucket 2 because there is a programme around it. A university research group using QR funding to partner with an NHS trust on clinical data science is doing strategic, applied work, but it sits in Bucket 1 because the state is hands-off.

I do not think my outstanding questions are unfair: who manages the boundary between Buckets 1 and 2? Who monitors whether foundational research fields are strengthening or weakening? Who connects research trajectory to strategic intent?

The old system did not answer these questions either, but at least it did not claim to. The risk I identified in November was that, despite the potential for it to illuminate our understanding of the research base, the bucket framework would materialise merely as “Frascati-with-branding” – a relabelled version of existing categories that resolves none of the real tensions. Nothing we’ve seen has yet mitigated that risk.

What the research base is actually doing

Everything I have described so far is about the framework. But perhaps the question that matters more is what is happening underneath it.

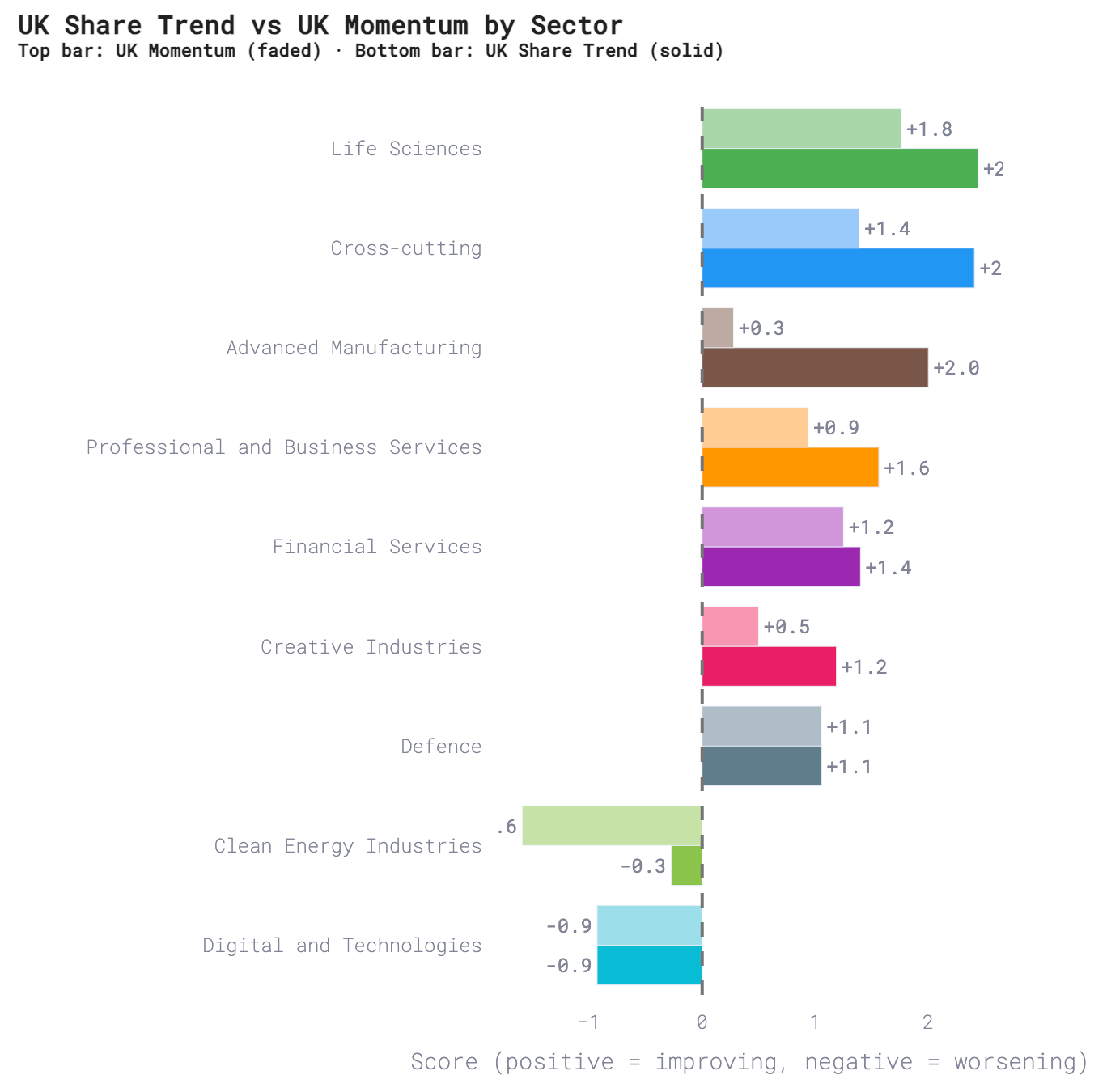

Using OpenAlex publications data, I mapped UK research topics against Industrial Strategy priorities to ask a specific question: do the sectors receiving the most policy attention have the research base to deliver? The answer is uncomfortable.

Clean Energy and Digital & Technologies are showing negative average research momentum – i.e. where the UK is losing publication share in more fields than we’re gaining it in. These are precisely the sectors receiving the largest Bucket 2 and 3 allocations and carrying the most political weight. Life Sciences priorities, by contrast, show strong and consistent positive momentum – the research base appears well aligned to the policy ambition. But for the government’s two flagship bets, the foundational research trajectories seem to be moving in the wrong direction.

These are average scores across all mapped priorities within each sector, but the sectoral picture matters less than what sits underneath it. Within these sectors, some specific priorities stand out. Advanced materials has the worst trajectory of any priority mapped in the analysis – with the UK’s share going backwards in over half of the underpinning research topics.2 This matters because materials science is not confined to a single sector – it is foundational to batteries, hydrogen storage, semiconductors, and composites, propagating across Clean Energy, Digital & Technologies, Defence, and Advanced Manufacturing simultaneously. The Advanced Manufacturing programme in Bucket 2 will presumably fund some materials work within its portfolio, but the SRO for Advanced Manufacturing is very likely not responsible for the health of materials science as a discipline – only for the materials work that falls within their programme’s scope.

The same is true for the Clean Energy SRO, the Defence SRO, and so on. Each programme funds its slice; nobody aggregates the picture. If UK materials science is declining across the board – as the publications data suggests it is – the bucket framework has no mechanism for noticing, because the decline is distributed across several programmes and partially hidden inside Bucket 1’s responsive-mode grants. This is exactly the kind of cross-cutting problem that a governance framework, as opposed to a budget classification, would need to be able to see.

What’s more, the field-level trajectories I have identified are not the product of unstoppable global forces. In 73% of the 4,516 topics analysed, the UK trends do not follow broader patterns among the major science blocs – Europe, the United States, and China. This indicates that UK-specific factors – our funding decisions, our talent policy, or our institutional choices – are driving UK outcomes.

In other words, if we are going backwards in key areas, it’s likely down to us. The corollary is that UK policy can make a difference: these trends are responsive to domestic choices, which makes it all the more important that the governance framework is designed to make those choices intelligently.

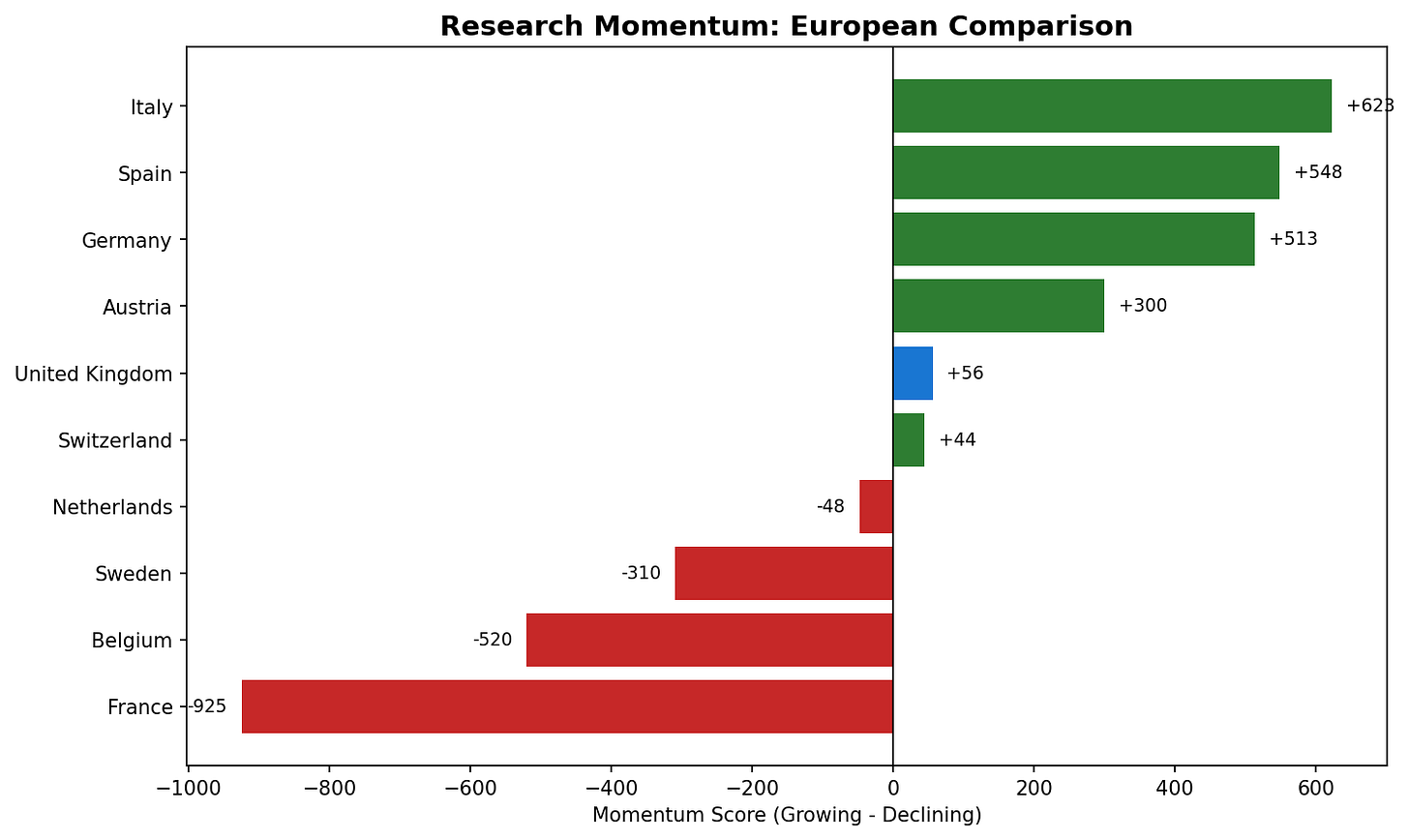

The European comparison sharpens the point. Among major European research nations, Germany and Italy are thriving – gaining momentum in 500 or more topics beyond those they are losing. France is in serious trouble, losing momentum in nearly twice as many topics as it gains. These are countries that operate in the same European funding and policy context. The difference is likely driven by country-specific choices about research funding, university governance, talent, and international collaboration.3

The UK, at +56, is barely net positive. We could go either way. The research governance frameworks we put in place will determine our fate.

What would have to be different for this entire thing to work as it should

So where do we go from here?

What follows is not a comprehensive reform proposal. But based on the analysis above, a governance framework that functions as more than a budget classification would need at least five things.

First, QR should be recognised as multi-bucket funding – because that is what it is, as the CEO himself told parliament. This does not mean carving QR up between the buckets, which would be both impractical and undesirable. It means the governance framework should acknowledge that block grant funding sustains capacity across all three modes, and that the Bucket 1 headline should not rest on the fiction that QR is undifferentiated curiosity. QR is, by design, the closest thing the system has to a genuinely enabling and strengthening investment, and classifying it alongside infrastructure, talent, and facilities would better reflect what it actually does. Therefore, QR should be moved to Bucket 4.

Second, the boundary between Buckets 1 and 2 needs hard-edged criteria. When does research move from “curiosity-driven” to “strategic”? Currently the answer seems to be: whenever someone in Swindon creates a programme. Without objective criteria, bucket assignment is a proxy for revealed political preference – the stuff the government has decided to wrap in a programme gets classified as strategic, and everything else is curiosity by default.

Third, someone needs to own disciplinary health. The Explainer creates SROs for each sector programme, and Chapman told the committee there is now “one person responsible” for each programme area. Good. But who is responsible for advanced materials research? For the upstream physics that feeds quantum? For the disciplines that don’t map onto Industrial Strategy sectors? Richard Jones has observed that only around £800 million a year goes directly to research councils for applicant-led proposals – out of an average annual UKRI budget of £9.6 billion. If the councils’ direct stewardship of responsive-mode research is this small relative to the total, and if the cross-UKRI programmes are absorbing an increasing share, then disciplinary health monitoring becomes extremely important.

Fourth, Bucket 4 needs real governance. £8.4 billion of infrastructure, talent, and international investment cannot be dismissed as a pro-rata residual, however convenient that might be for the ongoing presentation of a “three-bucket” framework. These are shared platforms on which all three modes depend, and they require their own accountability and planning logic.

Fifth, comparison simply must be possible. Not because backward-looking accounting is intrinsically valuable, but because a framework that cannot be measured against its starting point cannot be held accountable for its results. The select committee chair was right. Chapman has acknowledged he could provide high-level mapping and has committed to audit trails when specific choices are made. Both should be delivered. The committee should hold UKRI to it.

Close

The bucket framework was a serious proposal that deserved serious implementation. Lord Vallance brought genuine intellectual ambition to the role of Science Minister, and the desire to create a clearer relationship between public money and public purpose is the right instinct. Ian Chapman has been admirably direct about the choices UKRI faces, and his willingness to own difficult decisions personally is a genuine asset.

What the framework got, however, was a budget reclassification that inflates the curiosity headline with QR, sorts directed programmes into new headings, and defers the governance architecture to documents not yet published. Meanwhile, the research base is shifting in ways the framework cannot see: strategic sectors with weakening research foundations, cross-cutting capabilities with no institutional owner, and a position among European peers that is barely net positive.

The spring strategy documents – promised by the Explainer – are an opportunity to remedy this. But they will only do so if they engage with the governance questions that the Explainer avoided: how the buckets operate differently, who manages the boundaries, who monitors what is happening to the research fields that feed the programmes.

The data show the UK’s research trajectory is not entirely determined by global forces, and so UK-specific choices will drive outcomes. The question is whether the governance framework is designed to make those choices well. On current evidence, it is not.

The framework might usefully start by internalising a truth that Richard Jones articulated on BlueSky last week: “the motivation for a scientist to work on a particular problem doesn’t have to be (and often isn’t) the same as the motivation for someone to fund it.” The buckets have been constructed entirely around the funder’s motivation – directed or undirected, commissioned or uncommissioned. They are silent on what the research actually is. A governance framework worthy of the name would need to see both sides.

This analysis draws on a systematic assessment of UK research momentum across all 4,516 research topics in the OpenAlex database, comparing UK share trends over 2010-2024 against 46 comparator countries and mapping results to 203 Industrial Strategy priorities. The full analysis, including the detailed methodology and an interactive data explorer, will be published separately.

“Going backwards” here means the UK’s share is falling - either steadily over time or rapidly in recent years - or the UK’s share has stalled after a period of historic growth.

This international dimension matters beyond UKRI's own spending. It will also be critical for interrogating the merits of UK association to FP11, the successor to Horizon Europe. And it would be really good if we could take a future association decision on the basis of much better evidence than we had available when we decided to associate to the last framework programme.