Erasmus and the government’s opportunity mission

Is this a £570m diplomatic concession dressed as social policy?

[NOTE: In this post, I’m taking a departure from R&D policy to talk about the announcement that the UK will be rejoining Erasmus+, the EU’s youth mobility scheme, from 2027. If you are not interested in this, feel free to skip. Normal business will resume in my next post!]

So, to great fanfare and no small amount of surprise, the UK has announced that we will be rejoining Erasmus. Many across the UK higher education and further education sectors are delighted about this “fantastic news”.

Why has this happened? The government wants you to believe this is about “breaking down barriers to opportunity” (Stephanie Peacock MP), “breaking down barriers and widening horizons” (Nick Thomas-Symonds MP), and “breaking down barriers to opportunity, giving learners the chance to build skills, confidence and international experience” (Baroness Smith). Lots of agreement across those three ministerial quotes!

Well, there is certainly something to be said for breaking the link between a child’s background and their future success, and about disadvantaged learners finally getting the chances that were once hoarded by the privileged few. But if we apply an opportunity lens to the Erasmus decision and actually look at the money, the distribution, and the alternatives – the story starts to fall apart.

The weight of the money

The headline figure is that Erasmus will cost British taxpayers £570 million for the first year, with the 30 per cent discount reportedly applying only in that initial year. The Times reports that future annual costs could rise towards £1 billion, and the Telegraph pegs it at potentially £8 billion over the lifetime of the agreement. For some, this sum of money is “practically nothing” for the “huge benefits” it brings. I’d suggest this reflects a certain loss of calibration about what public money means.

There are 3,166 state-funded primary schools in England located in neighbourhoods in the highest child-poverty quintile (IDACI deciles 1-2). Divide £570 million by that number and you get roughly £180,000 per school. Nobody in government is offering that trade – but it’s a useful way to feel the weight of the money. What does £180,000 mean for a primary school in Knowsley or Jaywick? It means teaching assistants, speech and language therapists, family liaison officers, after school clubs, musical instruments, books, sports equipment… the list goes on. Multiplied across the most deprived or “left behind” areas in the country, we’re talking about serious impact.

Or we can consider the government’s own fiscal choices. The Office for Students distributes around £300 million annually to widen access and participation to English higher education each year – a figure that is in decline. The new international student levy, which ministers have explicitly linked to reintroducing maintenance grants for disadvantaged students, is expected to raise around £445 million in its first year.

So: one year of Erasmus is nearly double the English WP budget and comfortably exceeds the entire maintenance grant envelope that the government is creating a new tax to fund. These comparisons are uncomfortable.

And what about the old HEFCE supplement that supported students on overseas exchanges – around £2,315 for full-year placements? This was finally scrapped in the OfS allocation for this academic year. Are we simply robbing Peter to pay Paul?

The distribution question nobody wants to answer

Defenders of Erasmus rightly point out that it’s not just for university students. The scheme covers schools, FE, vocational training, adult education, youth work, and grassroots sport. The vocational and schools elements are real and potentially valuable.

But breadth of eligibility is not the same as breadth of uptake. The question is not “can Erasmus fund a hairdresser in France?” but “what share of UK Erasmus participation will actually be vocational versus university? And within each sector, what share will be disadvantaged learners?”

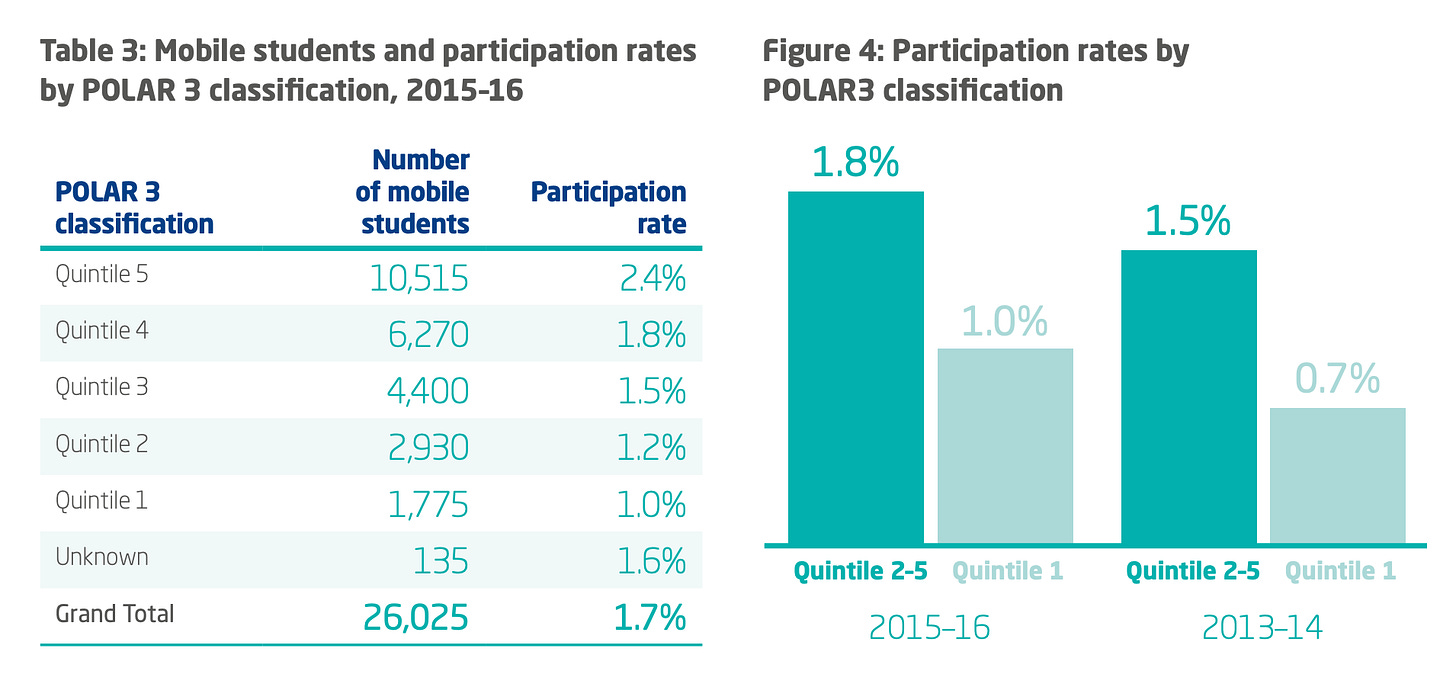

We know something about this from the literature, and it’s not reassuring. A JRC working paper on Erasmus participation in UK higher education found a negative relationship between the share of disadvantaged graduates at an institution and its Erasmus participation rate. In other words, universities with more disadvantaged students send fewer of them abroad.

A UUKi report on widening participation in mobility put numbers on the gap: in 2015-16, students from higher socio-economic backgrounds were sixty-five per cent more likely to be outwardly mobile than their disadvantaged peers. Care leavers participated at barely half the sector average rate.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Mobility requires capital – financial, yes, but also cultural. You need to know the scheme exists. You need to believe it’s “for people like you.” You need the confidence to apply, the resilience to navigate bureaucracy, the family circumstances that allow months away. The 2012 Riordan report on barriers to mobility found that money and language were the headline obstacles, but these were reinforced by curriculum inflexibility, patchy credit recognition, and thin institutional support. I’m sure lots of this was improving in the years before Brexit, but we shouldn’t forget that any system that makes mobility feel like an optional add-on for confident, well-off students rather than a normal part of study will reproduce existing advantages.

Yes, some working-class students do go abroad and find it transformative. I don’t doubt the individual stories – nor do I question that important work happened in non-elite institutions to coordinate Erasmus in a way that served disadvantaged students. But the existence of working-class beneficiaries doesn’t tell us about aggregate distribution. If 15 per cent of participants are from disadvantaged backgrounds and the scheme is life-changing for them, that’s still a scheme where 85 per cent of the spend goes elsewhere. The question is never “can this help some disadvantaged people?” but “what share of the spend reaches them, and is that share better or worse than alternatives?”

Which brings us to the comparison the sector doesn’t want to make.

The Turing counterfactual

The Turing Scheme was created after Brexit as the UK’s own outward mobility programme. It has been relentlessly criticised – too small, too transactional, and too much a reminder of what we left behind after we left the EU. But here’s what Turing actually delivers, according to DfE’s published data for 2025-26: of 35,248 placements, 61 per cent (21,411) went to disadvantaged participants, at roughly £2,500 per placement overall.

Crucially, those numbers are published. Turing reports actual spend, actual placements, disadvantaged share by sector, and geography. We can scrutinise it, ask hard questions about it, and see whether it’s working.

The government says Erasmus will benefit “up to 100,000” people annually. Crudely split, that’s £5,700 per head – more than double Turing’s unit cost – but we get no transparency on who those participants actually are or what share will be from disadvantaged backgrounds. Perhaps this will all come out in the wash – but right now we’re being asked to spend nearly twice the widening participation budget on a scheme whose distributional impact is both questionable and poorly evidenced.

The structural problems Erasmus won’t fix

As Jim Dickinson notes on Wonkhe, the UK’s problem was never just low participation overall – it was patterned inequality with compounding effects. Students with overlapping disadvantages had even lower rates. And the barriers are structural: tightly specified curricula, professional accreditation constraints, the UK’s general failure to do credit transfer properly, and insufficient support infrastructure in many institutions.

Erasmus membership alone won’t fix any of this. Without curriculum reform, functioning credit transfer, or requiring outward mobility to feature in access and participation plans, we’ll likely see the same skewed uptake we saw before Brexit – just at greater public expense.

Dickinson is right that if ministers really want this to work as an opportunity intervention, they need a proper strategy inside DfE, proper incentives or targets for universities, and progress on the structural blockers. Otherwise, a future government will look at disappointing participation figures – in volume or access terms – and conclude the money was wasted. Given what we know about who historically participated in Erasmus, that conclusion may not be wrong.

Why is this happening?

If the opportunity case is weak, why is the system so convinced that this is a great idea?

A cynical reading is that the people making and influencing these decisions are disproportionately the people who benefited from programmes like Erasmus. When your career has moved between Russell Group universities, Brussels think tanks, and Whitehall policy roles, European exchange doesn’t feel like a class-skewed luxury – it feels like the essential infrastructure of an educated life. Does the possibility that your own formative experience might not be the highest-return use of public money even compute?

That’s unfair, of course – but the sector’s criticism of Turing was also very revealing. It was framed almost entirely as “less money than Erasmus” and “Brexit damage” rather than engaging with whether Turing’s design principles – explicit disadvantage targeting, and clearly published outcomes – might actually be better for an opportunity agenda. Turing made the distributional choices visible and therefore contestable. Does Erasmus simply launder them through the warm glow of European solidarity?

The honest version of this debate

Rejoining Erasmus is a legitimate diplomatic and geopolitical choice. It signals alignment, repairs relationships, brings the UK back into European educational networks, and has genuine soft power value. The institutional benefits are real, and so I should not be surprised that sector leaders are delighted about all of this. But if that is the argument, let’s make it openly and let it be judged on those terms.

The opportunity case is, at present, much thinner than the rhetoric suggests. It invites an audit. On outcomes, Turing currently looks like the more effective tool: majority participants from disadvantaged backgrounds, full transparency, and clearer sectoral targeting – and at less than half the unit cost.

If ministers want to make the opportunity case for Erasmus, they should commit now to the same transparency standard: actual spend, actual placements, disadvantaged share, sector split, and geography. They should require outward mobility to appear in access and participation plans. And they should explain why they cut the existing overseas mobility supplement in the same year they signed a £570 million cheque to Brussels.

Otherwise, this whole thing is a gift to politicians who want to reason, in a motivated way, about whose opportunities our systems and institutions really care about.

Well researched piece… I’m pleased to see the UK rejoin ERASMUS+. However, not at any price. The minister has committed to a transparent evaluation after 10 months of data before writing any further cheques out to Brussels as part of the next EU Multi-Annual Financial Framework. As we saw with the recent collapse of UK participation in the EU defence fund, unfortunately there are elements in the EU that just see the British Exchequer as a cash-cow, whether that is handing over billions to take part in defence procurement; offering subsidised higher education (i.e. plans to give EU students home fees status in a future youth mobility scheme); or paying millions to the French gendarmes for their own policing of the Pas De Calais. It seems old continental habits die hard: the UK govt. is seen as a soft touch and always has been.

Really interesting article. Thank you …